Michael Branca - Fine Art

Coming to Terms with the Term

Coming to Terms with the Term: Art as an act of self-definition for Gen X

By Aimee Curl

Maine Times

October 26, 2000

The press release for the Generation X show at Portland's Danforth Gallery promised the exhibition of work by artists age 19 through 35 would surprise, and perhaps "even disturb" me. But I walked away from the opening neither surprised, nor disturbed. Perhaps this reaction is symbolic of my own membership in this ill-defined generation of "apathetic slackers." Of course, such monikers are hand-me-down terms coined by workaholic baby boomers. (Oops, sarcasm, another Gen X identifier.)

Wandering through the cavernous gallery, I felt oddly comfortable with many of these themes, and was impressed by these diverse and sometimes haunting expressions from artists of a selected age group.

In its beginnings, Generation X was recognizable by punk-rock attitude, spiked hair, body piercing and leather clothes, which in the eyes of the more "sophisticated" generation, instantly identified them as non-productive members of society. Then at the dawn of the information age, this group of punk rockers morphed to include techno-geeks and Sega junkies.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the Gen X exhibit at the Danforth is that there is little to do with computers or the Internet. Classical illusions abound, from Michael Branca's portrayal of the Last Supper, where bug carcasses replace the saints, to Kimberly Potvin's image of the crucifixion, with a bare-chested woman taking Jesus' place on the cross. Yes folks, Gen X has more on their minds than Web sites and video games.

There are even still-lifes of fruit and a host of black and white photography. And instead of focusing on the future - as the Xers are supposed to do - some of the artists hearken back to their youth. Jeffrey Barnett's "Basement," is a very '70s depiction of two young boys sitting in front of a console television, surrounded by pea-green carpet and brown- and orange-striped furniture.

Jen Kodis's black and white photos of a child in a dentist chair and a crowded sledding hill are warm, unmistakable images.

The former produced an instant knot of recognition in my stomach. The families sledding seemed reminiscent of a more simple time, prior to this information generation.

Mark Bessire, visiting curator of the show and director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts at Maine College of Art, says he was surprised to see so many historical references. "In such a techno-generation, it's interesting that so many artists have fallen back onto domestic culture." Bessire, who at 36 barely misses the Gen X cut-off, says he didn't expect to see images like the repetitive portrayal of a car in Todd Munro's "Migratory Herd." There were also few video entries or Internet art; another surprise, he says.

"The whole Generation X thing is a way to market to a certain group. Having a Gen X [exhibit] seems at odds with looking at an artistic movement, but at the same time, the media looks at the technological aspect of this generation. And this is real labor-intensive work. It's interesting that art is going the other way."

Bessire believes this exhibition to be the first of it's kind. It was inspired by Ted Halstead's August 1999 article in The Atlantic Monthly, in which he described Gen X as generally lacking in public commitment, conservative in spending, but liberal in thought. Because this is an important election year, Helen Rivas, director of Maine Artists Space, the organization which runs the Danforth, decided to test Halstead's theory and provide a forum for dialogue about the issues of concern for this generation.

They received nearly 100 entries, drawing work from New York to Newfoundland. Of the 35 featured Gen X artists, 10 are from Maine.

Artist Michael Branca, who came to the advisory board of MAS as a result of his work with the show, says he likes the idea of having a forum for himself and his peers, though he finds the term insulting and can't think of any positive connotation in the stereotype.

"I'm not a fan of the term Gen X," he says. "But that's been part of the whole experience, coming to terms with the term. It's a media-generated and proliferated term to place people into a box, saying you're all a bunch of slackers and unfocused people. I don't agree with that. I hope this work by different people who are very focused and motivated will help redefine the generation."

Does Branca find any of the art disturbing? Well, there is one piece, George Arnold's "February." The work is comprised of a light table covered with tiny sealed packets of the artist's blood, each squished into an abstract, back-lit form. "That could be disturbing to some people," Branca says. About the exhibit Branca noted that "You're not seeing what Gen X is here. Hopefully people will be surprised and effected by a broad spectrum of work done by young artists."

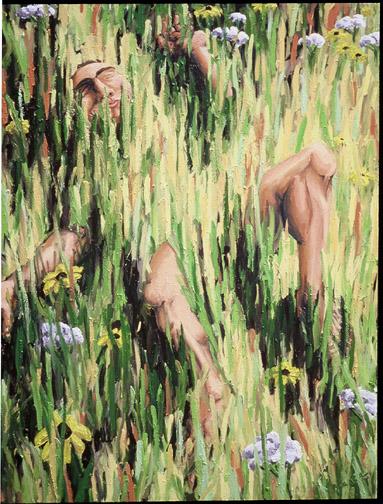

Branca says his two pieces in the show represent both ends of his work's spectrum. "The Last Supper" bug diorama, is one of his many bug pieces that depict a recognizable scene; "Oneness," is a giant oil painting of a man pleasantly engulfed in grass and flowers which reflects his "serious" painter side.

Jennifer Benn of New Hampshire is one of the few artists here to depict computers in her work. During the panel discussion that kicked off opening night, Benn explained why she thinks computers are both "beautiful and stupid."

"I'm presenting the machine as something to be examined. I don't quite believe all the hype," Benn said. "Computers are pompous and over-inflated. They're beige and visible and people depend on them so much. I know the geeks that program them. They have no social skills. They don't go outside. They have big butts and eat Chinese food. I wouldn't trust them with my money. They're put up as infallible, but they're not."

It wasn't long before the panel was asked how they felt about their place in this "unknown generation." Artist Michael Angulo of Standish made light of the stereotype.

"It's refreshing to see people actually entered the show," he said "Gen X kids were supposed to have played video games and that's it."

Canadian artist Erik Edson says the same connotations exist across the border. "Maybe I'm purely a Gen Xer in that I don't like to be called part of some group. I never really felt part of a generation. In the sixties, a hippie might pass someone and say 'hey, brother.' We don't do that. There's a disassociation between us."

Candice Smith Corby of Boston says she can't put her finger on who belongs to the X crowd. "How do you come up with an age bracket? Where does it start? Where does it stop? I tried to come up with a new name and I just came up with more questions."

MAS's Rivas says that contrary to pop culture myth, her experiences with the unknown generation have been positive. "I work with a few of them and they seem to have a seriousness and a desire to learn. They want to improve their working skills to get a better job. They speak in a straight-forward manner," Rivas says. "Perhaps there's a difference between them and Gen Xers who aren't artists."

Whether or not the stereotypes stick, there's no denying the interest in this age group and their art. Response to opening night, which was a crowded affair, was overwhelmingly positive, yet varied, especially among folks from older generations.

At least one person experienced the press release's promise to disturb. "I am an artist and a formalist," said Don Thayer of Portland. "A lot of things that are far out psychologically disturb me." He didn't want to give his age, but said with a smile that he collects social security. It was the piece composed of the artist's bodily fluids that got him.

"I hope no one bled to death to make it," Thayer said.

Steve Shapiro, 61, said he enjoyed the show, but didn't find anything particularly out of the ordinary about it. "This could be any generation," he said. "There's a variety of imagination and techniques. It doesn't surprise me, although I wasn't sure what to expect."

All told, the Generation X exhibit is not about stereotypes. Not surprising, considering that many members of this group don't associate themselves with an overarching theme or lifestyle. What it is about is giving young artists a forum to express themselves collectively in a way that has not been seen before. To this purpose, the Portland show serves to delight young and old alike. Perhaps Mark Marchesi, 23, of Portland said it the best while processing what he characterized as a "very good" exhibit:

"I don't want to comment on it as a Generation X art show. I don't buy it. It's just a name they had to give us."

Publicity

Home

All artwork copyright Michael P. Branca

|